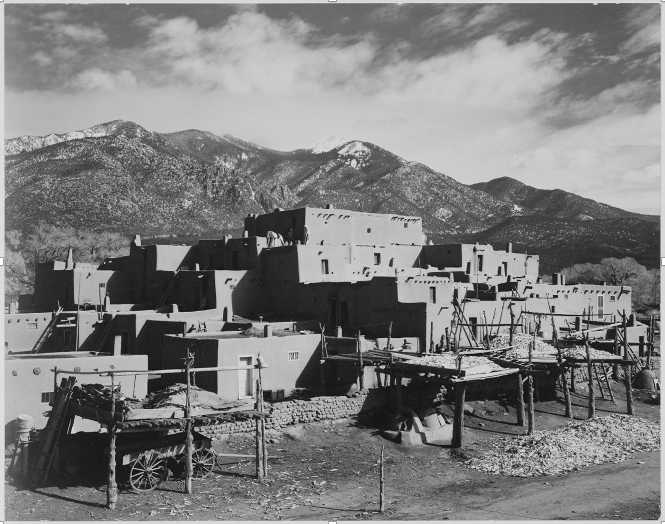

Leaving Taos Pueblo

As we were waiting for the bus, it occurred to me that I hadn’t thought to ask the name of the mountain chain behind the north houses—the peaks that bring a certain grandeur to the pueblo and punctuate views from the town. Boarding, I asked the tiny old bus driver whose torso curled toward the wheel like a cooked shrimp. He pointed behind me and said, ‘Ask him.’ I took my seat and saw him enter, casually clad from head to toe in black—hoodie, pants, trainers. He was a Red Willow person, neither young nor old, who probably lived on the reservation outside the pueblo. His face looked faintly grubby and he had lost several teeth. Leaning forward and looking across the aisle—now in a prawn-like posture myself—I delivered the question. Phlegmatically he pointed westward to a shorter segment of the range and mumbled a response I couldn’t make out. After requesting that he repeat the name and hearing another indistinct utterance, the enquiry was dropped in favour of embracing the bracing scenery racing by.

A minute or two later, unprompted, he announced, ‘We just call that one George Washington.’ Puzzled, I looked through the window. Nothing registered. ‘Look at the top, over there.’ Indeed, nature had stamped a portrait. Snow covered the lower easternmost peak in such a way as to create an unmistakeable image of the first U.S. president. In earnest I exclaimed something like, ‘Wow, that really does look like George Washington!’ Without missing a beat he asked, ‘Do you want to buy a dreamcatcher?’ and fumbled the two simple pieces he held in his hand, one adorned with navy ribbons, the other with dark brown, onto the bus floor. He scrambled to pick them up. I felt his embarrassment.

©F. L. Blumberg 2025

How did he end up peddling dreamcatchers to tourists? As far as I know, though their hoops are often made of pliant red willow reeds, the talismans themselves are not part of Red Willow culture, as they are in Ojibwe and other northern Native populations. Instead, to keep away bad spirits, they will paint their doors red or consult a healer.

In the inn where I was staying, I had noticed a coffee-table book, Pueblo People: Ancient Traditions, Modern Lives. On the cover, a grandfather, dressed in a turquoise plaid button-down shirt and slacks, and granddaughter, wearing a native-print dress, smile lovingly at one another. This man, however, down on his luck, scraping by, seemed to slouch astride a borderland, part of a generation that could neither live inside the pueblo nor thrive outside of it. Who wants to go camping every day? he might quip. Why not try to make a buck rather than hunt for one? At the same time, he came across as someone who—sad to say—did not get the hang of modern living so much as its hangovers.

I was not really in the market for a dreamcatcher, so I said sorry, but no thank you. That’s okay, he replied, then adjusted his sitting position to something more restful and pulled the hood over as much of his face as he could. When we approached Our Lady of Guadalupe Church parking lot, I got up. Passing him, I told him to take care. You too, he said.

That afternoon, George Washington followed me everywhere. For half a block he would disappear but I would turn a corner and there he would be again, watching me, like the New Mexican Mona Lisa. It was strange; every day for a week I looked at that mountain and had never noticed the face. Now it was all I saw.

Even more haunting was the question of how long this name had been in circulation amongst the Taos Pueblo people. No one I met in town seemed to know of the figure on the mountain. I learned only that it was known locally as Taos Mountain and formed part of the Sangre de Christo range. Nothing online suggests any recognition of this pareidolia either, despite images going back to the 1920s that show the face. (You can discern it in Ansel Adams’s 1941 photograph, for example.)

‘We just call that one George Washington.’ Was this an inside joke—some black humour—that he let slip out of the pueblo? One can imagine grievance behind this waggish observation, maybe from a younger, politically conscious tribesperson, the likes of whom we met at the pueblo, who might have said:

‘Even our mountain cannot be fully ours, imprinted by the so-called founding father who lived hundreds of years after Columbus, who himself lived hundreds of years after we, the Red Willow people, built our dwellings in its vicinity. In 1970, we got the land back; but his likeness up there shows that someone will always be monitoring us on our own land, imposing their ways on us.’

Now, when he crosses my mind, it is as the man who has lost his grip on dreams. Good natured but troubled. Pathless. I wonder, What did he dream of as a boy after the rituals at Blue Lake, on the slopes far below Washington’s sight? What made him smile as a teenager and feel the spirit of life pulsate? What did he learn from his grandparents? How would they guide him now? I am reminded that, wearied as he might be, he maintains native wit, and while bleary-eyed, he carries a culture of vision.

I wonder, too, what giving him ten George Washington banknotes for that dreamcatcher would have accomplished. Maybe something to help him along. Hardly enough to do any lasting good. I would have bought it not to protect my soul while asleep but to guard his when awake. For those times of open-eyed nightmare, when the nerves are under frenzied attack and the pangs tell you to reach for any ready remedy. It would have been more a prayer than a purchase, and it feels now as though I ought to have made it. But we never got to the price. Who knows? For the sake of poetic justice, he might have wanted an Andrew Jackson or two.