Shitamachi: The Low City

When Tokyo was known as Edo, the low city was home to the townspeople that kept Yamanote, the high city—the abode of the shoguns, aristocrats, and their retainers—functioning and entertained. Here dwelled the artisans, the restaurateurs, the shopkeepers, the actors and geishas—the kinds of people who could make a city come alive with hustle and bustle. They lived shoulder-to-shoulder in cramped quarters, by the low-lying edges of the Sumida River, in danger of being swamped by floods or destroyed in a fire started by a stray naked flame. As if goaded by the precariousness of fortune, the low city had a raw vitality that the high city, formal and spacious, did not, and it powered innovations in Edo’s popular culture, both in kabuki and Ukiyo-e, the bold art of woodblock printing that flourished between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

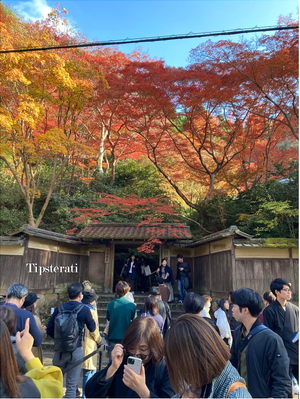

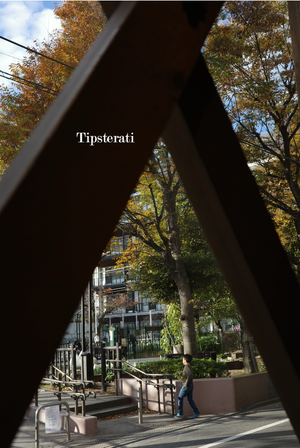

Today the low city is still there, but its heyday is over and its star has dimmed. Physically it has changed. World War II bombings destroyed the maze of lanes and wooden buildings. The commercial and cultural power it once held has also shifted westwards towards the high city. Yamanote has appropriated the low city’s dynamism. Nowadays we go to Shibuya and Shinjuku to sense Tokyo’s tremendous energy. The low city has become quieter and calmer. Parts of it are covered with tall buildings too, but the vibe is more low-key than the high-rise urban frenzy of the new commercial centres of the high city. Other parts, lucky to escape damage during the war, like Yanaka or Ningyocho, are still quaint and charming. These areas have become relics, bastions of the old ways. Their scale is still human; their pace slower. The roads are narrow, sometimes winding, often with intriguing side lanes or alleys that tempt the wanderer.

There are streetside gardens tended to by green-fingered residents who have expanded their tiny home plots into public space.

A variety of streetside gardens ©Wendy Gan 2024

Small businesses that have a long history continue to sell their specialties: amazake (sweet rice wine), rice, or tofu. One makes tsukudani (side dishes) in an old wooden building, another sells senbei (rice crackers) amidst interiors that look unchanged since the 1950s.

Old shops in Yanaka ©Wendy Gan 2024

The young have rediscovered the quiet joys of the low city, and you will find homely cafes, cozy eateries, and trendy greengrocers side by side the heritage businesses. You may also stumble across—in the middle of a residential street—a workshop run by young craftspeople specialising in leather goods for the modern city dweller or even an artisanal gelateria creating both Japanese and more cosmopolitan flavours.

The sign of a Yanaka gelataria and a sample of their offerings ©Wendy Gan 2024

Some might lament this seeming gentrification, but I think the new generation of business owners is simply continuing in the shitamachi spirit. The point is that in hyper-capitalist, ultra-modern Tokyo, the appeal of the low city today is its art of slow but purposeful living. The young come to the low city to work and play (as do we) because we all sense here a way of life that does not feel out of kilter, but is appropriate to the human. The high city dazzles with its wealth and high-tech novelties; the low city feels like home.