The Flow of Water in Seoul

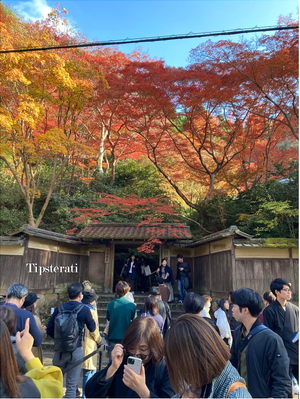

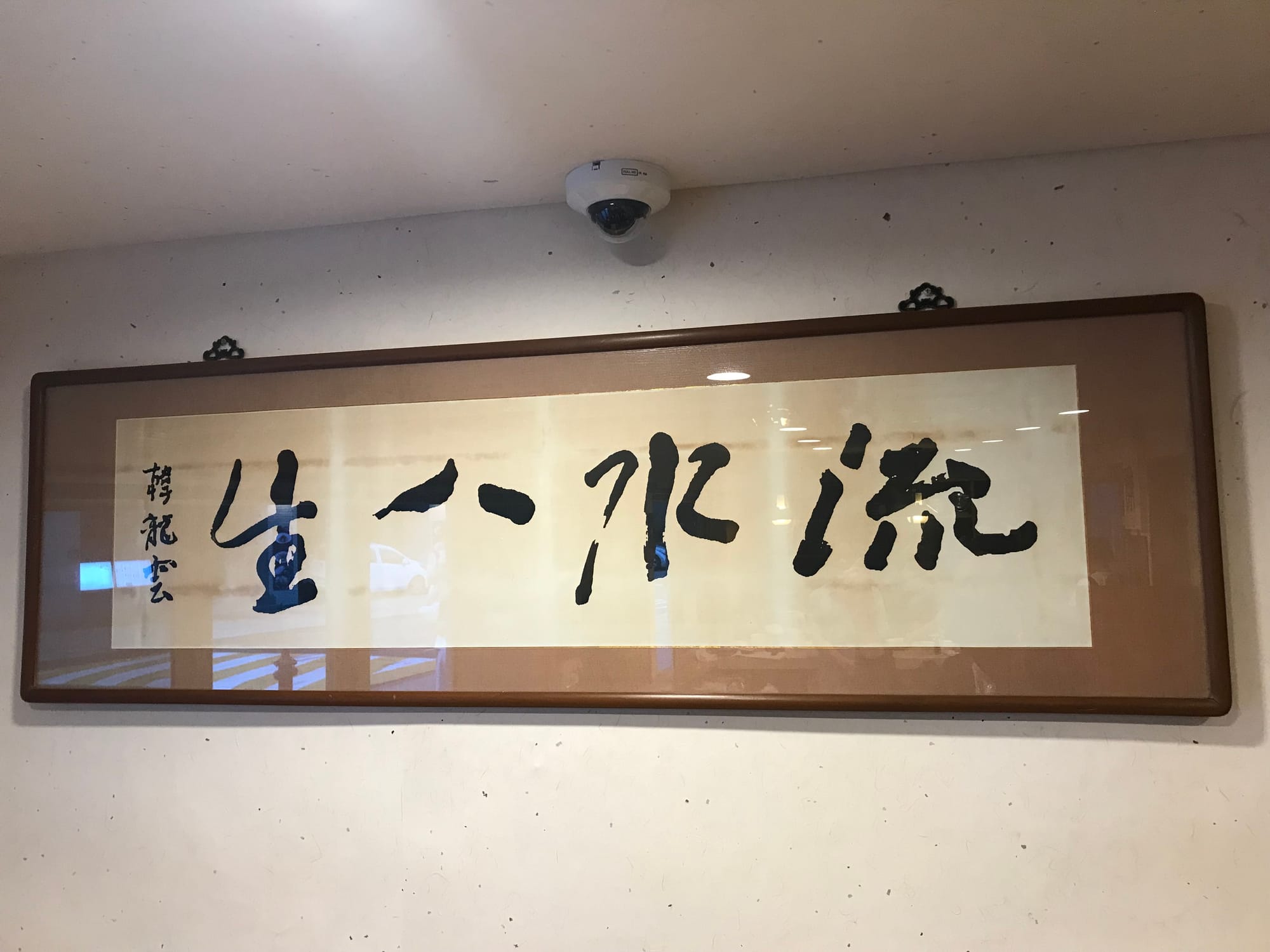

The Second Best House in Seoul (서울서둘째로잘하는집) is a shop in Samcheongdong serving tea tonics—traditional brews made with fruits, nuts, roots, and herbs. It is called the second-best house in Seoul, I suppose, to suggest that only one’s own home can provide better comfort and more caringly made concoctions. It has been around since 1976; long enough that, for many, it lives up to its name. On the back wall hang two objects: a framed print of a calligraphed line and a modest round clock that, over time, has earned its vintage look. The line, taken from the writings of Han Yong-un, one of Korea’s eminent twentieth-century poets and courageous advocate for her independence, contains four Chinese characters: 流水人生 (flow water person life). Perhaps the most natural translation would be ‘Human life is like running water.’ A friend pointed it out while my back was to it; thereafter I grew thirsty to understand the logic of this simile—what the flow of water might signify.

©F.L. Blumberg 2024

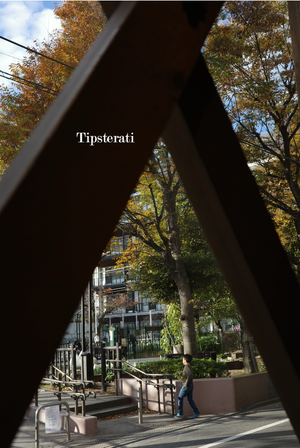

One reason the figure occupied my mind was that, whenever the opportunity arose, I would walk along Cheonggyecheon, the nearly 11-kilometer stream that bisects the north and south of Seoul. To reach one of the walkways on either side of the water, you must descend a couple of flights of steps. Once you do so, you have somehow both escaped the city and reached its heart. It serves as a meditative respite, suitable to being alone with one’s thoughts, and at the same time a lively promenade, good for small social gatherings. Here you will see the water serenely flow and the people walk by in just the same manner.

The first time I walked down to Cheonggyecheon was at night. Jazzy notes from a saxophonist greeted my ears and an elderly man dancing by himself gently whirled before my eyes. Not only mine. A number of young women sitting on the ledge overlooking the stream would turn to glance at him now and again, admiring a soul so free. Though you yourself may not be caught up in so elegant a rapture, strolling along the waterway does let your spirit unfurl a bit. Down here you are more you.

©F.L.Blumberg 2024

So it was here, during late afternoon walks, that I contemplated Han’s aphorism. It remains to me a droplet whose source is unknown. The interpretations that follow are merely those that have drifted to mind.

Imagine that you are looking at a stream. The water you view proceeds swiftly. It never slows down long enough for you to keep it in sharp focus and it will outrun your vision. Motion, obviously, is one of the essential properties of Han’s figure. Take away the flow and we are left with the rather amorphous and stagnant idea that ‘Life is like water.’ We might imagine water to be clear and familiar, transparent to our gaze. Yet, no matter how limpid and pure, we cannot apprehend water as it courses. We can apprehend only that it courses. Thus he might be implying: Because human life is plainly before us, it seems graspable, but because it moves rapidly, it is ultimately inscrutable. It is right in front of us, yet what do we really understand of it? Try as we may, it will always glide out of view or slip through our fingers.

Or perhaps Han's adage encompasses a slightly different idea: not that life's meaning is unknowable but that its moments are difficult to appreciate as we would like to. On this view, the problem is aesthetic as much as existential: we desire that the stream remain as it appears to us right now. But this is impossible. We cannot walk about in wonder while everything else has been paused in a freeze-frame.

Only in fantasy. “The Sound of a Stream,” a poem by one of Han’s contemporaries, Kim Yeong-nang, depicts this longing for a lasting moment, also in the image of moving water:

If only it would stop and linger, like the wind.

I wish the stream would flow, so I can feel it brimming full,

then stay a while like a painting, before flowing on again.

If only we could explore everyday evanescent beauty as we examine an artwork! Kim's wish, I venture to say, is widely familiar. It certainly is to me. Almost any sensation that brings me real pleasure leads me to think (usually while I am in the midst of enjoyment), Why cannot this last longer? Why cannot I carry on in this moment, tasting just this, touching just this . . .? Any time there is a perception to behold I am reminded that it cannot be held onto. But, were life to stop its cursive propulsion, its blind rush onward, it would not be life. It would be a specimen.

If we cannot have an eternal moment, a contradiction in terms, as a consolation we would like for certain impressions to crystallise in our minds and make us feel blessedly alive for at least some time after they have made their initial mark. We wish to feel as the English poet William Wordsworth did when he returned to the picturesque ruins of Tintern Abbey:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years.

It is not always easy to have Wordsworth's faith. Sometimes, especially while travelling, an impression does not feel . . . enough. It seems stamped not crisply enough on my mind. I linger before a building, a painting, a flower. When I simply have to leave lest I am left behind or miss the connection to the next locale, I take a flurry of photos and a deep breath, and in a final moment do my best to ‘drink it all in’. But what do I end up imbibing? The effort to emblazon an image on my memory never quite works. What stays with me is fragmentary. And I am more likely to recollect feelings associated with an experience than its physical details.

Phenomena are fleeting and our lives, the totality of our moments of perception and reflection, are mortal. The Hindu epic, the Ramayana, also compares our life to water in motion: “Life, like a flowing river, does not return to its source” (bk. 2, ch. 105). The idea is that our lives move only toward death; there is no way to stop, let alone reverse, its course. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus is best known for having said that one cannot step into the same river twice. Everything is in motion and changing. Neither the water nor the person stepping into it will be the same. Han was a Buddhist monk (and water has long-appeared as a figure in Buddhist teachings); might he have meant something similar to Valmiki and Heraclitus—that life is ever-changing and transient?

Last, consider a Taoist perspective. Perhaps the line can be read: ‘Human life should be like running water.’ We must take the cue from this element and live naturally; sleuth out sluices, find the channels that can carry us and keep us going. In Reasons for Korean Independence, Han writes, “the popular feeling (for independence) is like water flowing where it will and Korean independence, like a rock rolling down from the top of a mountain, cannot be stopped until it reaches its destination” (tr. John Christopher Houlahan). Here the idea is that the forces of nature make events inevitable. The passion for liberty will find its expression, just as the water of the Cheonggyecheon wends its way from westward mountains through the center of Seoul to the east of the city, aptly ending up in the Han River (한강).

The grey heron stands on one leg atop a marbled stone jutting above the Cheonggyecheon. Still and poised he stands, except to preen and scratch every minute or so, as people pass by—the joggers, the new couples crossing stepping stones, the eager tourists, the businessmen hopeful about their prospects, the old women who remember this very stretch from their childhood (the same but not at all the same now, they must think), the office worker heading to the steps beneath the overpass where she can at last sit down with her phone and zone out. None approaches his stoicism, and as if to prove it, he homes in on some small fish wiggling by but lets them carry on uninterruptedly. Only a mere mortal would leave this perfect perch for a mere morsel.

A few passersby notice the bird and point him out to their friends. But they need to keep moving. The heron needs to stay. He does not live in the moment; he is the moment.

Tonight, a man in his early 60s, drunk, caught sight of him, crouched and shouted at him. I do not know what he said but it sounded like a futile command from one who knows deep down that his size and might will never force grace, never control a soul bestilled. Soon the heron turned, craned its neck downstream, before flying off with an eldritch screech. Perhaps we would not know what to do with the moment, were it to last forever, vulnerable to our hazy gaze.

The clock ticks. Time flows, as does the tea; the customers come and go. One step inside this place with its old-school vibes and one might think, ‘Here, time has stood still.’ But it is a place where everything is flowing: the welcomes, the conversations, the memories.