Hirosaki & Shirakami San-chi, Aomori

Welcome to Tipsterati, the Zuihitsu newsletter where we offer you behind-the-scenes information and tips on exploring the areas we feature in our photo essays.

This is a free preview. Future issues will only be for paid subscribers.

“Aomori?”

My Japanese hair stylist in Singapore utters this in surprise. He doesn’t say it, but I can imagine him thinking, “Why would anyone want to go there?” He certainly doesn’t think much of the place.

Aomori is the northernmost prefecture on Honshu island. North of it, across the water, is the better-known island of Hokkaido. It shares a similar climate to Hokkaido—harsh winters and cool summers—but it lacks brand recognition. Mention Hokkaido and the international visitor to Japan can picture snow, skiing, ice cream, and lavender fields. Mention Aomori and many will draw a blank. Indeed, we would not have thought of visiting Aomori until K, a Japanese friend of mine, put it into our heads. We knew it as the land of apples and the birthplace of contemporary artist Yoshitomo Nara, but little else besides. Some quick googling after K had mentioned it brought up the primeval beech forest reserve Shirakami San-chi (a UNESCO World Heritage site) and the Nebuta, or lantern-float festivals in Aomori City and Hirosaki. The reserve promised some beautiful hiking; the Nebuta festivals, with their large illuminated floats and carnivalesque atmosphere, looked exotic. We were intrigued and, seeing that K was happy for us to tag along, we decided to join her, together with her husband and another pair of mutual friends on a three-night trip to Aomori.

I’m not sure what I was expecting when we arrived in Shin Aomori (one stop away from Aomori city) to pick up our rental van. After crowded Tokyo, there was a mass of brilliant blue sky and barely another human in sight. It felt as if the world had emptied out and we were left to our own devices. For company, there were the apples outlined in the street railings. I could not shake this feeling of desolation, even when we pulled into busy rest stops for a snack or when we dined in a cavernous hall full of guests at a hotel. In Aomori, you are always alone with the elements. It is not a cause for despair; there is no room for despair here. It is just how it is. Standing by the sea, hair whipped into a frenzy, eyes barely able to open from the fierce sun and wind, or walking in silent awe amid ancient beech trees, Aomori reminds you that, once urban fripperies fall away, you are only a figure in a landscape. It is a truth that is discomfiting.

Still, you are a figure in a landscape of surpassing beauty. This is why the desolation I sense in Aomori is of a strong, pitiless kind. Aomori is wild. It is stirring. It is lonely, but it is the loneliness of the one who stays behind to care for the rice farm in deep winter, to fish the rough waters, to walk the old forests. A proud loneliness. You don’t stay on in Aomori unless you are stubborn and strong. You don’t stay on unless you find the forests and coastlines wistfully and painfully lovely.

Aomori has mystery and a certain power. You feel it as you gaze in the pure, blue-green waters of Juniko. You feel it in the still depths of the beech forest. You feel it by the rugged sea. You sense it in the way a small city comes together for a summer festival of giant incandescent floats, held not just for a single night but for seven consecutive nights.

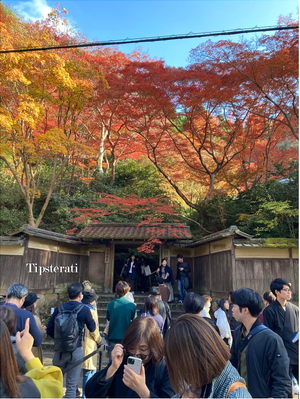

I must admit I came away not knowing if I really liked Aomori. It doesn’t have the delicate and refined charms of Kyoto. It doesn’t engage and stimulate you as Tokyo or Osaka can. It lacks the relaxed and vibrant warmth of Fukuoka and Kyushu. But Aomori haunts me in a way that none of these other places have. I still see the unique colours of the Juniko lakes. I remember the hush within the beech forest and the steady, relentless rush of the waves on the coast. I recall the air of desolation. Then the swirling, glowing floats of Hirosaki glide in and the darkness is dispersed.

Some additional notes on the Hirosaki Neputa Festival

The earliest recorded mention of the Hirosaki Neputa festival dates to 1722. Its modern form began in 1914. Since then, it has been halted twice: once during the Second World War and again during the Covid-19 pandemic (2020, 2021). In 1980, the Japanese government named it an Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property. Whenever I hear this I think: that is a . . . Comprehensive and Fitting Albeit Lengthy Designation.

The proposed origins of Nebuta (the term I will use to cover the festival not only in Hirosaki but across Aomori Prefecture) are sundry. Some explanations suggest overlapping traditions; others may be legendary. According to one account, in the late sixteenth century, the founder of the Tsugaru clan, a feudal lord who ruled over not only Hirosaki but all of northern Aomori Prefecture, visited Kyoto and, as a statement of regional pride, hung up a two-square-meter lantern during Oranbon, the festival which honours the spirits of ancestors. Some hold that it goes back even further: to an early Heian shogun, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, who orchestrated bamboo flutes and taiko drums to divert the enemy’s attention during battle. Or perhaps he devised the placement of enormous lanterns atop a hill to intrigue the enemy and capture them when they came to investigate the curious bright figures. Then again, some say that he ordered the construction and display of immense warrior dolls—with soldiers hidden inside, some conjecture—to terrify an approaching enemy.

More commonly now one will hear that Nebuta has ramified from two coinciding summer festivals. One, a ritual tradition called nemuri nagashi (or nemuta nagashi)—'the driving away of sleepiness'—was an early July event that, according to the Japan Tourism Agency, first involved "carrying leaves and lanterns, and cleansing one's body of the fatigue and drowsiness of the summer by passing those negative states onto these items." After a few days, on the seventh of July, the leaves were set adrift on rivers. The word nebuta probably comes from Tsugaru dialect words for 'sleepy': nemute or nepute (in standard Japanese nemui). From the custom of nemuri nagashi comes the idea that the Neputa festival reflects anxiety about the harvest and therefore its participants aim to drive away demons that lure farmers into sleeping too much during the summer.

The other festival thought to have contributed to modern Nebuta practices is Tanabata, a.k.a. Hoshimatsuri (star festival), itself derived from China’s ancient Qixi festival, an eighth-century cultural import to Japan. The stars Vega and Altair are imagined as separated lovers, a weaver princess and cowherd, who may meet only once a year. In this version of its origins, Nebuta’s floats develop from the lanterns sent into river streams at the end of Tanabata. At some point, people made larger and more elaborate lanterns, which were called nebuta, and the event was renamed Nebuta Nagashi before becoming known in the eighteenth century as the Nebuta matsuri, as it is known today.

To learn about the making of the floats and all things Neputa, you can visit Tsugaru-Han Neputa Village, near Hirosaki Castle. The complex also includes a crafts centre, where one can take classes; daily performances of musicians playing the shamisen; a restaurant serving traditional Tsugaru dishes; and a garden and teahouse.

On Apples

Aomori is the land of apples and they are everywhere. The rest stops along the highways will have apple ice cream, apple cider, as well as apple juices made from a variety of cultivars for the connoisseur to compare: from Fuji to Jonagold to Orin. You will find complimentary apple juice in your hotel fridge and at all hotel meals. Hirosaki even has an apple-pastry-tour itinerary you can follow (we had no time for this sadly).

Logistics

Getting to Aomori is easy enough with Japan’s high speed shinkansen trains. Trains leave regularly from Tokyo. But once there, renting a car is recommended, especially if you are planning to visit Shirakami San-chi to hike.

You could get by with taxis if you are a group of 2-4 sharing costs, though it will be more expensive than a rental car. Your hotel can arrange taxis for you, so do speak to the reception and ask for their help. Some hotels may even be able to provide free pick-ups from local train stations, so it’s worth checking with them in advance.

Where to stay

If you wish to attend the Aomori City Nebuta festival in early August, you must book your hotels early. We tried in May and failed to find anything. We were lucky, however, to find vacancies at the elegant ryokan Asobenomori at the foot of Mount Iwaki and it even offered a Hirosaki Neputa package, which included a sumptuous early dinner and a shuttle bus to Hirosaki for the festival and back again. It’s very handy if you don’t have a car. Their website has some English, and for sections that are only in Japanese, Google Translate came to the rescue. I managed to make bookings without a hitch. The onsens at Asobenomori are quite lovely too, so make sure to spend time relaxing in their hot springs.

We also spent a night at a Koganezaki Furofushi Onsen, which has hot spring baths right by the sea’s edge. The views from the baths are wild and stunning, as are the sea views from the rooms. The hotel, however, is a touch dated and, being rather large and anonymous, feels like a machine for processing the holiday masses.

In Shirakami, we stayed at Shirakamikan. It was the most hostel-like of our accommodations in Aomori, but we just needed something close to the beech forest reserve. The food though was excellent and it was a superb example of how even relatively plain hotels with unfussy facilities will take pains to provide meals that feel worthy of a Michelin-starred restaurant.

Water Sports Activities

I’d like to get a quick plug in for A’Grove Canoe & Rafting, which is a short hop away from Shirakamikan. Their whitewater rafting programme was so well put together and so enjoyable that I feel that anyone making their way to Shirakami must also give them a go. The staff, in spite of their limited English, will take extremely good care of you.