Window of Confusion, Window of Enlightenment

I came to Genko-an, like so many others, to visit a hall featuring two windows whose names promise much to the viewer: confusion and enlightenment.

All I really knew before going was that one window was a quadrilateral, the other a circle. As I conceived of it, they must have been designed as an experiment in perception, a philosophical challenge. Surely the underlying idea was that, because it is often difficult for us to discern between ignorance and wisdom, between what leads to our suffering and what to fulfillment, these windows were purposefully crafted to inspire reflection on what the right perspective on life looks like. The round window might represent enlightenment, I conjectured, because of the importance of cyclicality in Buddhism. In any case, I assumed that you would need to look at both openings to understand each. Enlightenment, insofar as it exists at all, is something you reach or come to or find. It is not given to you. There must be darkness before a dawning.

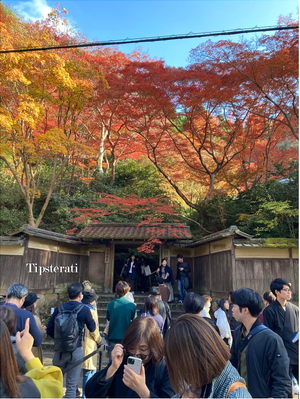

As it turns out, however, almost everyone arrives enlightened (a few seconds of internet searching on the way to the temple will do the trick). Nobody cares for confusion. Well, very few do. It is understandable. Have we not had enough of perplexity, error, and ignorance? After all, they are our natural and default states. They are mine, at least. So, almost anytime, even during the height of fall tourism, you can walk right up, sit right down, and have the centre view of what is called Confusion but, by most modern urban standards, makes for a pleasant scene. In late November, it featured a still-green small maple; a partial view of a larger maple, fully yellow; a hedge and some little green plants whose names I do not know. The popular disregard of this window, whose name is 迷いの窓 (mayoi no mado)—sometimes translated as the Window of Delusion—was itself a bit disorienting to me. There I was by myself, while a metre or so away, several rows of queues had formed to get a peek at enlightenment. Yet there were two windows, on the same wall, at the temple to which we had all journeyed. They are presented as a pair. Why limit the encounter to one?

At any rate, much to my befuddlement, the crowd desired only illumination. No fools, they hasten to the Window of the Correct Answer. Who can blame them? I can, a bit. For, ironically (and paradoxically), in their pursuit of instant gratification, they bring delusion to the Window of Enlightenment precisely by not bringing an awareness of delusion to it. Its name, 悟りの窓 (satori no mado), is sometimes translated alternatively as the Window of Realisation or Spiritual Awakening. But how can we grasp life’s true nature while ignorant of our ignorance? Without the benefit of contrast, all they get is the Window of the Pretty Scene. And, when they get there, they view it only through a digital eye, whether the enormous lens of a chunky camera or a smartphone. They are not there to contemplate but to record having been to the Famous Beautiful Place. Doubtless some of the photos will be crisp and accurate, some may rise to the level of artworks themselves, while others will be remembrances that no one will remember to look at after a week’s time.

Meanwhile, what are they missing? What can be said for bewilderment? First, observe the top of the window-frame. Vertical lines—wooden bars—form the horizon. For a split second, you wonder whether you inhabit the world’s most elegant prison cell. Below, the window seems just barely rectangular, almost a square. It presents an incongruity that is ever so awkward to the eye. On either side of the window and reaching to the ceiling is a yukimi shoji, or window divider, that is itself divided into many latticed boxes, strongly hemming in the view, multiplying the sense of enclosure. You learn that it is not solely the shape of the windows, or even what can be seen through them, that makes for an enlightening or confusing sight. Through the opening, as I have said, there is an agreeable, if flat and plain, view. The overall impression, however, is of being boxed in. It is said that the four corners of the rectangular window represent the banes of human life: birth, old age, illness, and death. While that sort of symbolism must be taught to the viewer (a 90-degree angle is not obviously symbolic of suffering), nonetheless anyone can leave this section of the wall with an intimation of life’s limitations. In a way, the proliferation of points does create a mood of pointlessness.

When it is finally your turn in front of the porthole-like window and you have your meeting with Zen Insight, you feel the subtle pressure of all those behind you waiting to get their chance. Their presence can create anxiety and, well, confusion: How long may I behold enlightenment? What is the temple etiquette on this? Or are we operating instead on Instagram etiquette? What if I am a Late Awakener and need time to understand what I am seeing? An already-enlightened person would, perhaps, ignore the crowd and take his time. But maybe I am here because I have not attained that level of composure yet!

I badly want the room to be a solitary meditative experience. But then I remember: I am no monk. I am not even Buddhist. Why am I getting so worked up about serenity? And did I not choose to visit Genko-an for the beauty of the windows as much as for their edifying potential? All about the temple have I not snapped pictures too?

So, harried but humbled, I take a deep breath and try to take it in. The round window differs from the rectangular in that its frame is of darker wood, creating a bolder outline and more substantial contrast, as though you look through a lens to find a more sharply bordered snapshot. Nothing else surrounds it on the wall. We get a glimpse of the garden that feels both natural and artificial, alive and frozen, as though captured forever in a gargantuan locket.

The realisation of the round window is that, while the circle is just as bounded a figure as the rectangle, it gives the impression of suitable measure, of satisfying proportion. It allows one to be immersed in the moment, not thinking of life’s encumbrances. Somehow there is an eternity in the transient present. That is, when the perspective is orchestrated just so. It is entrancing but also can seem too neatly packaged or perfectly rendered, like a centrefold in Better Koans and Gardens or a Zen-Autumn-in-Japan snow globe.

I left the Window of Confusion thinking about the confinements of human existence—which constraints can be countered, which cannot. It reimbued meaning into that bromide: how can we think outside the box? I left the Window of Enlightenment with the faint memory of a congenial perspective. Its well-rounded view presented greater depth of field, which in turn created a sense of stasis, of momentary perpetuity—a curious paradox. It was soothing but the effect did not last. Maybe this was an intentional lesson in Sōtō Zen. Or maybe the crowd was right after all: it is just a lovely vista.

The mind behind the windows devised not so much a trompe l’oeil as a trompe l’esprit.